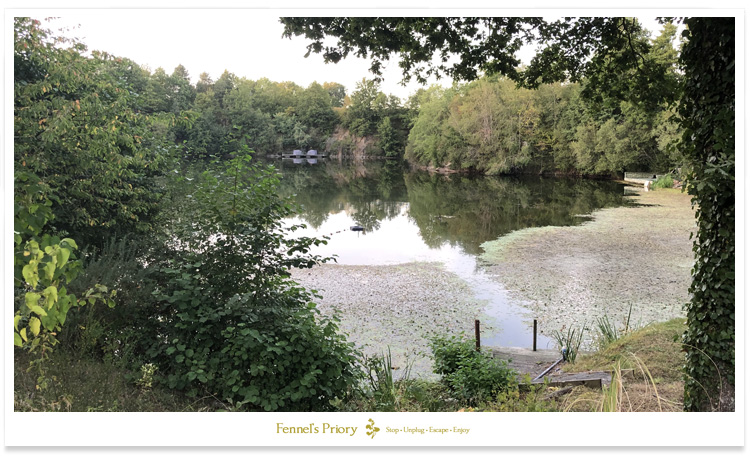

Quarry Bank Fishery - Part 9

Fennel continues his 12-part series about fishing at the fabulous Quarry Bank Fishery in France, this time exploring the nature of the pool.

The nature of a carp pool

Sitting with Shaun, Tim, Neil and Lin, eating home-cooked paella, drinking red wine and watching the sun go down, had a calming affect on our mood, like putting one’s feet up and closing one’s eyes after a big Sunday lunch. We’d enjoyed a jovial day of banter and mickey taking, yet now we felt the slowing of day and the gentle tranquillity of night.

Being September, the twilight lingered as though it wasn’t sure whether to draw the curtains or turn on a light; the sun dipped behind the trees on the far side of the pool at around 8pm, and we had a whole hour watching the bats flitting in the gloaming before it was too dark to see each other properly. Eventually, as we heard a purple heron ‘cawk’ as it came in to roost beside the pool, and little owls trying to ‘weeow-woo’ us to sleep, Shaun said, “I think that’s our cue, for us to head to our beds and see if Mrs Carp will pay us a visit in the night.”

We said goodnight to Neil and Lin, then walked back to our swims. There was just enough half-light left for us to see to cast in, so once our lines were positioned, we retired to our beds to sleep off our aching sides and bellies full of fine food and great company.

The nature of night

Sleep didn’t come quickly to me; I lay on my bed listening to the crashing of carp and tail slapping of catfish upon the surface of the water, and the jolting “quaeeeeks” of a night heron that sounded like a young mallard had sat on a red-hot egg and didn’t know whether to jump up or give it another go.

I heard a distant church bell chiming on the hour. 10pm, marked by two slightly flat yet invitingly dull “doongks” that sounded like a dinner gong held too tightly in one’s hand. Then, silence. The pool, motionless and black, seemed to be brooding and building for something to erupt. But nothing moved, not even the wild boar in the woods. All except me was sleeping.

Eventually the moon rose above the trees opposite. It was bright but waning; an old moon, copper-butter in its weariness, adding warmth to the cool night sky. The air, too, was warm. And muggy. Too ‘sticky hot’ for a sleeping bag, or clothes that clung to my skin and could be peeled off like the skin of a bruised banana. So I slept on top of my sleeping bag, in just my shorts. This kept me cooler, but my sweat drew the attention of the mosquitoes present at the lake. Neil had said that there weren’t many. This was true, but the ones that launched themselves at me sounded like the drill of a deranged dentist.

I shone my torch and saw two banshee-like invaders, each about an inch across and as brown as the dried blood on a serial killer’s hatchet, flitting above me and deciding when to pounce and hold me down while the other guzzled from my veins. I flapped my arms in anger then turned off my torch, thinking that if they couldn’t see me, they couldn’t find me.

I drifted off to sleep, hearing what sounded like distant band saws and Formula 1 cars buzzing towards me through the woods.

I woke in the night, itching. My legs and feet had been attacked by the winged invaders and were throbbing like the neck of a hanged man. A shine of my torch revealed thirty-one hard, weeping, incredibly itchy purple lumps. My legs looked like they'd been pocked by tiny meteorites.

Being allergic to insect bites, I knew that by morning my legs would have swelled up to resemble an elephant’s ankles and my skin would be as tight and brittle as cellophane in a shop window. So I did the obvious thing. I tucked my legs under my sleeping bag and went back to sleep.

Sure enough, when I woke and tried unsuccessfully to bend my ankles, I discovered that the mozzies had done their worst and that I would have to hobble around until the swelling subsided. But I didn’t want to get up just yet. I was cosy and feeling the satisfying ache in my muscles that told me they were finally relaxing after months of tension.

Animal attraction

Lying on my back, with my head tilted to the right, I stared at the wall of the bivvy, observing patterns formed by shade and sunlight that moved gently as the trees and leaves outside moved in the breeze. They were hypnotically beautiful, a kaleidoscope of warmth melting the veil of night.

And then I became aware something else that was gently moving – like a cool pulse – on my left cheek. Being only half awake, I brushed my face with my hand and felt something scurry stickily forward, over my left eye and then settle again on my forehead.

“That was nice,” I thought, in my dozy state. “A morning cuddle, while I enjoy a lie in.” It didn’t register to me that I had a wild creature partially covering my face.

My companion and I remained motionless while I looked at the moving patterns on the bivvy. My right eye was enjoying the spectacle while the view from my left eye was obscured by something thin and bronze-green. Whatever it was on my face just lay there, perhaps wondering whether I was going to make it breakfast in bed?

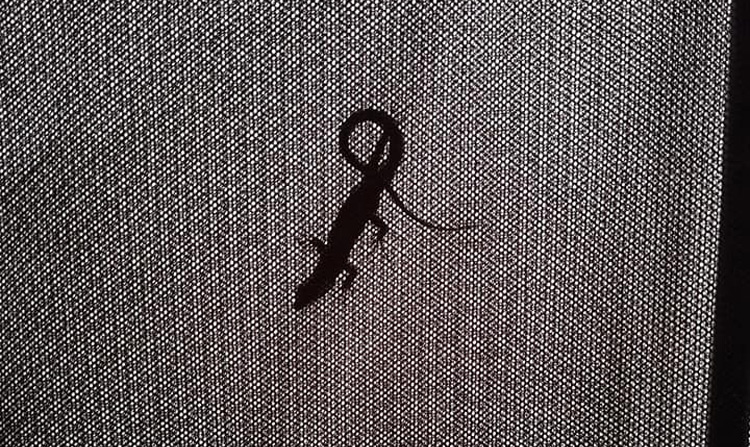

‘It’, I concluded, was one of the lakeside lizards, about the size of a newt, that had found warmth on my face during the night and, like me, was rather snuggly in its bed and not yet ready to get up. I drifted back to sleep knowing that, by the time I woke, the lizard would probably be gone.

Nature magnet

I woke and opened my eyes, seeing that the patterns on the bivvy were more joyfully playful and sparkly than before, now from reflected sunlight rather than that coming through the trees. I gently brushed my face and discovered that Lizzy had gone. She’d loved and left me, perhaps scurrying back to her other fella before he knew she was absent? Or maybe I was just a conveniently placed (and worryingly soft-headed) mattress upon which she crashed for the night? Who would know? Either way, I was just her warm brief lay. As she went about her business beside the pool, I was left stroking my fornlorned but silky-feeling cheek and forehead.

The same could not be said about my legs. I lifted the sleeping bag and saw that my feet, ankles and shins were as purple and bulging as an overripe aubergine and crusted yellow with dried and weeping cornflake-like ooze. I dared not touch them for fear of knocking the tops off the Vesuvius-like mounds of swollen skin, so I put my socks on my feet and pulled them up my shins as high as I could. I then replaced my shorts with a pair of trousers, thinking, "Out of sight, out of the doctor’s waiting room."

I remembered seeing some antiseptic wipes in the lodge kitchen. These would kill any nasties that were bruising my legs, so I’d use some of them at lunchtime and ‘be done’ with the mos-trauma and any thoughts of amputation. I was therefore in no rush to pass out at the thought of being dubbed the Elephant-legged Aubergine Boy of Quarry Bank. Beside, I had other priorities.

I was here to connect with the nature of the pool, and I’d certainly done that – albeit not with the sort of bites I’d hoped for during the night. Some of this nature had been so bold as to penetrate me, and one had stayed on for afters. All I’d had to do was lie there, knowing that they would get their pleasure without me moving a muscle.

Yup. I was an inherently satisfying, out-and-out nature magnet. A gigolo for those in a flutter or needing warmth. Juicy by night, oozingly smooth in the morning; but left with a throbbing itch for the rest of the day.

Lizzie was never far from my thoughts, or my tent.

Lizzie popping back to say hello.

Natural appetite

I checked my watch and noted the time: 10.30am. I’d missed most of the morning, so I quickly checked my phone to see if Tim or Shaun had reported any activity via WhatsApp.

Shaun had been catching a variety of fish on float-fished sweetcorn, including perch and a jack pike.

Tim hadn’t had any action in the night so had decided to recast his lines, only to find that all three were snagged against rocks. He’d been to see Neil who’d given him permission to use the boat to retrieve them, so had spent a good part of the morning paddling about. The movements of the boat, he felt, had probably disturbed his swim, so he was allowing it to settle before expecting any action.

Both Shaun and Tim had highlighted the ‘late morning’ prime feeding time at the lake, as evidenced during previous mornings, and were hopeful of some action before lunchtime.

Feeling the puss from my legs soaking through my socks, I decided that I’d better not fish on but rather go up to the lodge to wash and disinfect them. So I reeled in and limped along the lakeside path, saying "Good morning" to Tim as I passed him. I explained that I’d be away from the lake for a while so, instead of returning to fish, I would start cooking lunch at 12.30pm to give him and Shaun more fishing time. We planned to barbecue a feast of sausages and serve them with mushrooms crumbled with blue cheese, scrambled eggs with chilli flakes, Dijon mustard and piccalilli, beetroot salad, and a chunk of crusty French bread on the side.

As I hobbled up to the lodge, I couldn’t help but think that our lunch would look rather like my legs, so I decided not to tell the guys of my predicament. “More appetite,” I thought, “if they don’t see the human-sized version of what they’re eating.”

Teasels growing tall and strong, sheltered from winds at Quarry Bank Fishery.

Mother Nature

Having cleaned and nursed my legs, I grabbed a cool beer from the fridge and strolled over to the pagoda. I had a good hour before I’d need to start cooking lunch, so I decided to relax in the shade while enjoying the view of the lake. Neil had positioned a telescope in the pagoda for studying the lake’s wildlife, so I figured that looking through this would be a good way of passing an hour.

The pagoda at Quarry Bank Fishery, with telescope for viewing the bird life.

To my delight, Neil and Lin were in the pagoda when I arrived. They offered me a seat and asked me to join them in watching a pair of kestrels feeding their young. Neil, being in tune with the needs of nature, had observed earlier in the year that their nest had fallen on the cliff and been abandoned. So he’d built a special nest box for them that he’d bolted to the cliff during a daring semi-abseil down the rock face using ropes and a ladder. The box was now occupied with screeching youngsters that made a loud fuss each time their parents arrived with food.

The kestrel nest box at Quarry Bank Fishery, as seen through the telescope.

I mentioned to Neil and Lin that I thought the Quarry Pool had a female character, being so headstrong and decisive in her ways. Now, seeing the kestrels feeding their young, I realised that her femininity was maternal. The lake's ability to create and sustain so much life, so much wild life and so much contented domesticated life in the people who lived there or visited, meant that she was the life-giver, nurturer and protector. As Victor Hugo said, “A mother’s arms are made of tenderness and children sleep soundly in them.”

At the Quarry Pool, with its solid shielding walls of rock and 800 miles of separation between its waters and the furnaces that burned back home in the UK, I was reminded of William Wordsworth’s words, “A lake carries you into recesses of feeling otherwise impenetrable.” Rather like running home to mum after a tough day at school, I knew I would be greeted with outstretched and comforting arms whenever I visited this special place. Its wildlife knew this, I knew this, and Neil and Lin Shipman – having decided to spend the rest of their days here – especially knew it. As William Hazlett wrote, “We do not see nature with our eyes, but with our understandings and our hearts.” In this understanding we knew, as John Burroughs said, “I go to Nature to be soothed and healed, and to have my senses put together.”

The shielding walls of rock that protect Quarry Bank Fishery from the outside world.

Being in and amongst nature is life giving, life affirming, life forming, and, for me, life defining. When we gaze upon somewhere as remarkable as Quarry Bank Fishery, with its rich diversity of wildlife, we realise that Leonardo Da Vinci was right when he said, “Water is the driving force of all nature.”

Of course, we could quickly dismiss these analogies as clichéd descriptions of Mother Nature. But the sights and sounds in and around the Quarry Pool made it seem like a living, breathing, moving thing. Never had I experienced such richness of wildlife in one place. The pool and its surroundings were, quite literally, alive with pattering, scurrying, crawling, hopping, flapping, sliding, flitting, buzzing, gliding, crashing, and soaring. Even the wind, so common throughout our world, seemed drawn to the pool in delicate playfulness as it susurrated, rustled, and waved through the trees; eventually rippling, lapping and swaying the water, filling the quarry’s amphitheatre with the scents of flower meadows and the delicate mead-like taste of balsam and corn.

The quiet farmland surrounding Quarry Bank Fishery.

The extent of the nature reserve surrounding Quarry Bank Fishery, and the farmland beyond.

Looking in, looking down, looking up, and looking out: four perspectives enabled by a deep pool surrounded by high cliffs, with blue sky above reflected in the water below. The Quarry Pool really was somewhere to gaze upon the wonderment of nature. So, yes, I had a sense of ‘Mother Pool’ and ‘Mother Nature’ at Quarry Bank, both one in the same, both drawing us closer to our Creator. As Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote, “The love of a mother is the veil of a softer light between the heart and the heavenly Father.” Hence the appeal of the old Zen saying, “You should sit in nature for twenty minutes a day; unless you’re busy, then you should sit for an hour.” But sometimes we can go too long without our nature fix. Then, like the man crawling dry-mouthed to an oasis pool, we must get there with a sense of panic, to drink slowly, steadily, and for as long as it takes to feel the pulse of life returning to our veins and to that of everything around us.

Nature, reflected above and below, held in the film that divides one world from another.

Pooling our dreams

Thinking again of my preference for calling Quarry Bank ‘The Quarry Pool’, I mentioned to Neil and Lin about the significance of the word ‘pool’ as a verb rather than noun.

“People often overlook the meanings of the word 'pool',” I said. “It’s not just a name, it also means ‘to collect, gather, attract, and bring together, to share resources for the benefit of all involved.’ To me that raises its importance beyond the noun, which effectively means ‘big puddle’, and gives it a deeper sentiment.”

The Quarry 'Pool' had drawn us together, becoming the focus of our attentions, place of our friendship, and – like the wishing well into which we toss our coins – source and enabler of our hopes, dreams and investments. I explained that Late Bronze Age and Celtic peoples made similar votive offerings; ceremoniously throwing prized items into lakes to win the favour of their deities, because they knew that water was sacred.

“Maybe it’s similar,” I said, “to us anglers casting in our baits, hoping for a return that’s much greater than the weight of fish we might catch.”

“An offering to the gods,” said Neil, knowing that our ancestors’ acts were not that different to ours.

Looking down to the shallower end of the quarry, it was here that the stone was brought up to be crushed. One senses the calling to make a votive offering from this high elevation, though it's wise to stay well back from the cliffs.

Natural reverence

As much as we anglers love fishing, it doesn’t compare to our sense of reverence for water in all its forms. As W.H. Auden wrote, “Thousands have lived without love, not one without water.” This gives me comfort, knowing that if an angler becomes too old or weak to fish, just being beside water will sustain him.

For me, Quarry Bank Fishery was a place to pool my thoughts and ideas, somewhere to reflect, appreciate, and savour the present; somewhere sheltered from the world outside that, for me at least, had been more stressful, abrasive and exhausting than I’d ever have wanted. I was free of all that at The Quarry Pool. It’s ‘rock solid’ walls provided the defences I needed to allow myself to unravel and relax, to lower my guards so that I could breathe, sleep, and, if it helped, cry a little until yesterday’s efforts peeled free from my aching limbs and fell like dried leaves onto the water. And as they fell, I would remain swaddled, bud-like, in the protective fold of the Quarry, readying myself to unfurl anew, to be a brighter, fresher, and more vibrant person, to feel the sun and wind as if for the first time. Thus, our time at the Quarry Pool highlighted the organic cycle of life, where a few short days beside the water served as much needed recuperation from today’s relentlessly ‘on’ and evermore artificial world.

At Quarry Bank, life was real; and I was real. The real me; no veneer or walls, no pretences, no deflections; just me, Fennel: the gentle, sensitive and retiring writer who yearns to be left in peace amongst his beloved nature; where there’s no need to justify or prove anything; where I can just sit, fish and write, while observing, appreciating and savouring ‘the wonder of the world’. As Edward Abbey said, “Wilderness is not a luxury but necessity of the human spirit.”

Nature reclaims her own at Quarry Bank Fishery.

Custodians of nature

I sensed that both Neil and Lin were proud of the wildlife at Quarry Bank. Lin had planted her garden with lavender and verbena that attracted butterflies and moths, and Neil had erected bird boxes throughout the woods. I knew, from the moment I observed Neil’s quiet manner, keen eye and alert ear, that he was a countryman. He was used to being outdoors and, probably, grew restless like a swallow on a telegraph wire if he sat around doing nothing for too long. He had the classic look*, shared by young boys searching for birds nests to old men leaning on gateposts, of someone attuned to the ways, weathers, seasons and lore of the countryside.

*To the uninitiated, this look can come across as being quiet and slightly reserved. It’s not shyness, rather that the countryman knows the importance of inner stillness in helping him or her to listen, see and marvel at the natural world. And they might be a person of few words, too, until they speak on their favourite topics, as they know that the greatest message exists in the quiet moments when nothing is said but everything is understood. (In short, don’t expect an answer from a countryman straight away as he or she is probably distracted by the sights, sounds, wonders and delights of natural things; each of which is more exciting, interesting, commanding of their attention and worthy of their effort than most things you could speak to them about.)

Neil was ‘our sort’. A proper countryman. As was Lin, though there’s a bond between blokes that enables us to get a little closer, cursing without reprimand, trumping without consequence, and appreciating the whiff of each other’s well-worked ferrets. I knew, as we sat together gazing across the lake and ‘just looking’, that I knew exactly the question to ask.

“So, Neil,” I said, “tell me about the nature of your pool.”

“Oooh,” he replied, “now you're talking. As you’ve identified, Quarry Bank is more than a fishery. Lin and I want this to be a welcoming place, with greatest emphasis on ‘the place’. The fish, as quality and healthy as they are, are just one part of what Quarry Bank offers and represents. It’s a broader place, for wildlife and people, that has a strong sense of history and future – that it’s going to keep getting better as it matures and with it the sense of ‘mellowing’ that you’ve found appealing. Just imagine how you’d feel after being here for a month.”

“It’s also our home,” Neil continued, “and home to a wealth of wildlife, too. My great passion is the birdlife. The French word for bird is oiseau, pronounced “Wazzo!” like some 1970s Saturday morning kids TV show. It captures my excitement when I see the kestrels feeding their young, or glimpse a Bonelli’s eagle soaring overhead. The latter is so rare, with only 30 breeding pairs in France, yet it visits every year, passing on the thermals or eying up the lake’s rocky crags as a potential nesting site; but it gets chased away by the kestrels. The young eagles famously fledge great distances; those in this region of France have been known to fledge as far north as Denmark and as far south as Morocco. It really is miraculous how far they will fly during their wanderings. And we have hoopoes here, with their crown of feathers and ‘hoo-hoo-hoo’ calls; and golden orioles that like to bathe in the lake and peck at their reflections in the farmhouse windows. We have five types of owl: long-eared, tawny, little, barn, and scops; lesser and greater spotted woodpeckers, black woodpeckers (that have a red crown on their head), and green woodpeckers; white egrets, night herons, purple herons, regular grey herons; cranes and black storks; nightingales and nightjars; and of course the usual waterfowl such as coots, moorhens, grebes and mallards; and common garden birds such as blue tits, great tits, long-tailed tits, siskins, and goldfinches.”

“On the mammal front,” said Neil, “we have red squirrels, stone martens, hares, foxes – which have their earth in the cliff by the lake; deer and wild boar; four types of dormouse: field, garden (known hereabouts as Lérot), the black & white ‘Loir Gris’ edible dormouse, and the large edible dormouse that’s originally from the Mediterranean but was introduced to this area by the Romans; several species of shrews; the black-bellied hamster; hedgehogs; genets – a type of spotty wild cat that escaped from Africa; the European wild cat; coypu (known locally as ragondin) with their bright orange-red teeth; and four types of bat: horseshoe, long-eared, pipistrelle, and noctule. The latter swoop about the pine trees at the top of the lake and have a whopping 18 inch wingspan.”

“Insect-wise,” said Neil, “we have thirty different types of butterflies and moths, including large swallowtail butterflies, hummingbird hawk moths, and the truly enormous oak moth that’s as big as a robin in flight; we also have stag and rhino beetles, crickets which seem intent on chirping all night, and huge hornets that buzz around the treetops by the lake. Rarely, though, do we get any mosquitoes or gnats…”

Swallowtail Butterfly at Quarry Bank Fishery.

Feeling my legs begin to itch, I asked Neil: “What about reptiles and amphibians?”

“Loads of lizards,” he replied, “and black slow worms. And we have five types of snake: grass, adder, western whip, imitation (fake) adder, and the large but rarely seen Toulouse snake; we also have nine types of frog, including the common tree frog, Perez’s frog, and the tiny pool frog; oh, and some really big toads; also the marbled newt, and the black and yellow fire salamander.”

Grass snake at Quarry Bank Fishery

“Plant-wise,” said Neil, “we’re especially proud of our wild orchids and mature elms; plus we have lots of alder, cherry, oak, birch, goat willow, sycamore, pine and walnuts.”

Wild orchid growing at Quarry Bank Fishery.

Walnut trees growing strongly at Quarry Bank. They were introduced to this area of France by the Romans. I like to think that a Legionnaire had some in his pocket and, seeing the fertility of the soil, threw some into a roadside verge for the benefit of those who passed by in future years.

“Walnuts make some of the finest drawing ink,” I replied, “made famous by Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo’s sketches. Wouldn’t it be great if we could make some ink from the walnuts grown here, then use it to draw scenes and artist’s impressions of the lake?”

“Sure,” said Neil, “we’re not short of walnuts. I’ll sort you some and you see what you can make with them.”

“That’s a deal,” I replied.

The nature of the quarry’s past

“Of course,” said Neil, “the pool wasn’t always a haven for nature. It was once a violently noisy quarry, with explosions, heavy machinery and all manner of clatter that would have scared wildlife away for miles around. If you look closely at the rocks, you can still see dynamite holes in places.”

“Being a gardener,” I replied, “I noticed the subtleties of man’s influence away from the quarry as well; its legacy is there in the trees. There’s an oak next to the driveway, for instance, that was pollarded about 70 years ago, seemingly at the same time as mechanical diggers and lorries were introduced to the quarry and needed access to get down the drive. There’s a story in so many things, if we care to look and appreciate the archaeology around us.”

The pollarded oak by the driveway, presumably cut to allow passage of heavier machinery during the quarry's past.

“Talking of stories,” said Neil, “I was lucky to meet one of the elderly men of the village who remembered the lake when it was a working quarry. He wrote the story of the quarry for me in French, which I translated into English. It goes like this:

"A local man named Fernand M. Esmery noticed the quality of diorite stone (a hard crystalline rock with a composition somewhere between granite and basalt), which was ideal for crushing and using to create roads and paths. He established a small business in 1932 to extract it, employing 20 people. This was half of the employed people in the village. The quarry, known locally as La Viollets, was worked manually with pick axes, bar forks and shovels, with the stone being broken up with hammers, as these were the only tools available to the workers. The stone was loaded into horse-drawn wagons and removed from the site. It was very hard and demotivating work.

The diorite stone quarried for use in local roads and pavements. It has a black and white crystalline texture that geologists nicknamed 'salt and pepper'.

"Extraction continued like this for a year, until Fernand’s son Maurice modernised the operation by using explosives at the rock face. He also built a ramp down into the quarry and installed a small railway track upon it. Upon these rails ran small carts that were pushed by hand down to the face of the quarry. They were filled with rock and then pulled by winch back up along the railway track to the top of the quarry.

"The system evolved significantly in the early 1950s when the mechanical shovel – powered by a diesel engine – came and made removal of the rock much simpler after the explosions, thus increasing the potential of the quarry. This mechanical digger really was a sacred progress, as stone – including large blocks – could now be loaded directly into the carts coming down into the quarry, which was then taken to the top of the quarry and crushed and loaded into trucks by hand.

"A second quarry, called Bonneau, began nearby in 1951, extracting shale that would be used for the base of local roads and paths – but the harder crushed doiorite stone from La Viollets was always used to surface them, giving the paths and roads hereabout their distinctive pale look.

"In the mid-1950s, a lorry and loader system replaced the track and carts used in the quarry. Rock was loaded into bucket-like skips, to which chains were fastened to each corner and then hoisted onto the lorry by hand and taken to the top of the quarry where a new mechanical crusher was used to break the rock. The peak of extraction lasted for no more than five years, from about 1955-60, but during this time the diesel engines of the digger, lorries and crusher were running constantly, a blacksmith was continuously employed on site for making and repairing tools, as was the explosives expert who managed everything concerning the extraction of rock.

"The use of explosives was excessive – they were used not just to blast the rock from the quarry face, but to break up large rocks as well that were too large for the workers or machines to move. The engineer would drill a long line of holes into the rock, pop in sticks of dynamite connected by fuse cords, plug the holes with clay, then cover the lot with soil and turf. He’d then light a fuse wire and await an enormous explosion that shook all the houses in the village. The explosions were always at the stroke of noon. Local children would brace themselves for the shaking of their school at this time, and each other, fearful in the knowledge that it was not uncommon for the men of the village to be killed in these blasts and not return home to their families for dinner. (The man told me that health and safety was not what it is today, as he and his three schoolmates used to play in the quarry in the early 1950s, riding the carts along the railway tracks down to the base of the quarry.)

"A hydraulic loader was eventually used to replace the manual chain hoist that lifted the buckets onto the lorries. This increased performance and thus the volume of rock that could be removed from the quarry. The rotation of trucks leaving the site became considerable, and rock was dug in three or four levels taking 8m from the quarry face in this time, meaning that the quarry depth grew to a good 30m from the top of the quarry to the bottom.

"As the quarry drew deeper, so it became wetter with water flowing from the rock face, increasing mud at the bottom that prevented the lorries from carrying large loads. A sump was dug to collect this water, and a powerful pump installed to continuously draw water from the sump into the local River Sebron. But by 1961 the cost of running the pump and crushing the rock with diesel engines became too great, so the quarry ceased production. This was a huge loss to the local community, half of whom lost their jobs with the closure of the quarry. The pump was switched off and the quarry filled with water.

"The quarry, now a deep lake, was for some time used for diving training by the fire-fighters of Deux-Sèvres, but in 1975 the site was sold, fenced off, and a magnificent private residence built beside the lake.”

“Well,” I said, “the place sure is magnificent, and it’s evident that the quarry played a huge role in shaping and employing the local community and building the local path and road network. But I hadn’t realised that its story would be so dramatic, or so sad. I wonder how many workers lost their lives in the explosions? ‘Not uncommon’ indicates that it was too many, and the loss too frequent. Perhaps the love and abundance of life that exists at the lake today compensates for the grief and emptiness that must have dominated this place for so long?”

Neil, Lin and I sat silently for a while, thinking of the lake’s past.

It was in this quiet time that I remembered German philosopher Friedrich Schiller’s words, “Never the grave gives back what it has won.” But, looking out at the naturalised beauty of the quarry, I couldn’t help but think that the quote didn’t apply here. Sure, men’s lives were lost; but there was no sense of sadness or haunting at the lake. It was as if their love and energy had remained, always reflected in those who gazed into the waters. If so, it proved the epitaph attributed to Nicholas Evans, as seen on modern headstones: “Be still. Close your eyes. Breathe. Listen for my footfall in your heart. I am not gone but merely walk within you.” So, as Edgar Allan Poe said, “Even in the grave, all is not lost.”

Perhaps the water that poured from the rock did all the weeping that was necessary, and that by us being at Quarry Bank and appreciating its quieter times, we were honouring the men who lost their lives? As Friedrich Nietzsche said, “Only where there are graves are there resurrections.” So life had most splendidly and joyously returned to the quarry, a rebirth made worthy by Neil and Lin and all the wildlife that now called this place home, and the anglers who visited to experience its unique mix of past, present and future. It sounded profound, but by us fishing at the lake, and appreciating its legacy and natural history, those men’s lives were not lost in vain.

“Strewth,” said Neil, as he exhaled deeply. “The things we think of in the silence.”

The quarry face where so many lives were lost. Their spirits remain, reflecting so much life in the water's surface.

Looking down to the site of the old dynamite store. It housed explosives that created the quarry but took the lives of many men.

Custodian of nature

Oases of life, like those at Quarry Bank, are becoming increasingly rare; threatened by the choking grasp of industry, pollution and Man’s ignorant disregard for that which enables him to live. As with most things concerning nature these days, there’s a sobering reality to the plight and future of the natural world. But, like the widows who cried out in loss while standing beside the quarry, one has to calm one’s thoughts and pray for the future.

Our emotional energy is better invested in doing and thinking positive things, be they small or large, to help our precious wildlife. It might be as simple as erecting nest boxes for the birds, as Neil has done, or collecting and sowing seeds, nuts and seedlings to repopulate woodland and its verges, to provide habitat and sustenance for the entire food chain. In doing so, we know that our efforts must start at the base of the pyramid – improving the soil for all the little wrigglers that everything else depends upon.

And if we’re blessed with having a lake in the centre of this sanctuary, we can add extra layers by going deeper still: to all the subsurface plants, insects, fishes and invertebrates, even to improving the nutrients and oxygen levels of water quality that sustain aquatic life. Again, just like Neil has done at Quarry Bank.

Sometimes, though, it's not about action but simply sitting back and doing nothing, or keeping away, allowing Nature to show you how it should look and what should grow and be where. Then, once you can see her palette, you can help her to paint by doing all the big brushstrokes that enable her to fill in the gaps to create the broadest possible diversity of habitat for wildlife.

It's about life in layers, from in and beneath the soil, to the seeds, mosses and lichens on its surface; to the lush soft annuals and perennials that cover its floor, to the sub-layer of shrubs and climbers, finally to the trees that tower and all the creatures that exist within and above it.

As I looked around the lake, seeing more wildlife than I have experienced since I was a boy in the 1970s, I realised that in our ‘land of opportunity’, I find greatest prospect in the quiet places where there isn’t so much ‘land’ at all, rather in pools of water where one’s soul may drift free from the dust at our feet to glide upon and melt into the meniscus that separates one world from another, to exist in perfect balance, appreciating the natural tension between the elements of air and water, knowing that there is a world above and a world below, reflecting and concealing the obvious. We just have to see and act on its potential, as custodians of nature.

Shaun in contemplative mood, gazing out across the dried summer landscape next to Quarry Bank Fishery. It was so incredibly quiet; at the height of mid-day, the loudest things we could hear were the grasshoppers chirping in the fields.

Fence post at Quarry Bank Fishery. I wondered how many quarrymen had laid their hands on this over the years on their walk to work, and how many anglers will do the same as they take time out from their fishing to appreciate the wider appeal of the lake's surroundings.

In Part 10, Shaun, Tim and Fennel dig deep to catch more of the lake's carp.

Quarry Bank Fishery is a 5-acre water in southwest France, about a two-hour drive from Limoges airport. It is set within 14 acres of private grounds, which are sensitively managed for their wildlife interest. This makes it a haven for both anglers and fish. The fishery is available for exclusive bookings only, for up to five anglers.