Barbel Fishing on the River Severn

The heatwave in the UK continues. As I write (27 July 2018) we're set to have our hottest day on record, with temperatures soaring to 37ºC. But earlier in the week, three drops of rain fell somewhere north of Stoke-on-Trent. Precipitation had returned to the UK, albeit briefly.

Living as I do in North Wales, we had enough rain to turn our lawns into something resembling green grass. But the rivers hereabouts are desperately low – with equally low dissolved oxygen for the fish. So I’ve refrained from fishing. The trout and grayling, I feel, would struggle to ‘catch their breath’ after a fight against an angler. Instead of fishing, I’ve left my rod at home and gone for walks along the river.

Riverwalk

Last weekend I travelled slightly further away from home than usual, when I visited the River Severn near Bridgnorth in Shropshire. This is the river of my youth, to where I would cycle from my childhood home to fish at Arley, Alverley and Hampton Loade. It’s historic fishing country: Hampton Loade was one of the locations where the Angling Times arranged for barbel to be stocked into the Severn in 1956. (These were fish netted from the River Kennet in Berkshire. There were 509 in total, in sizes up to 9lbs.) By the time I started fishing the Severn in the early ’90s, barbel were the most prolific species in the middle river, with vast shoals being caught during matches. (All fish were returned to the water.)

The ‘middle Severn’ – as this area of river is known – and the valley in which it glides, is extra-special to me. It’s in my blood and bones, as my ancestors farmed this area for 300 years. And my great, great grandfather was a noted Bridgnorth pike fisherman, when he and his family weren’t working the land around Quatford and Worfield just outside of Bridgnorth. Hence my calling to view a river I’d not fished in twenty years.

The River Severn revisited

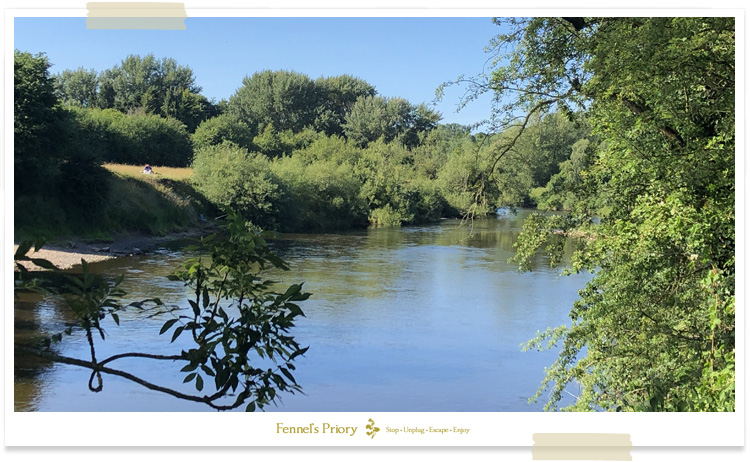

I drove to Hampton Loade, parking my car in the National Trust car park alongside the river, then walked upstream to the Birmingham Angling Association’s water and then downstream to the Kinver Freeliner’s stretch, reacquainting myself with once-familiar surroundings.

The river itself had changed little since my last visit in the late nineties. The deep pools and glides were still there; ranunculus weed was thick and lush, and the rapids and gravel runs chattered and tumbled with joyous vivre as they glinted and dazzled in the late afternoon sun.

Bankside trees had matured, especially the willows (which were now as tall as the alders), and the grass was much longer – a sign of less angling pressure on the river. Indeed, many of my old favoured swims were now forgotten and inaccessible. It looked less like Club water and more like that of a lightly fished syndicate beat. Where had all the anglers gone? To ‘carp puddle’ commercial lakes, most likely. ‘Chuck it, chance it, drink some beer.’ These overstocked ponds are not for me. I like wild fishing, especially in water that flows.

Small fish were evident; dace and small chub were rising to take flies drifting downriver in a mid-river crease. But I didn’t see the flash of a barbel in the river, or a fish rolling on the surface. They’d be there, hugging the bottom, beneath the weed where the water was shaded and cool.

The 'star act' were dozens of sand martins swooping the water and flying just two feet from my head as I walked along the high banks in which they were nesting. The holes in the riverbank cliffs were a blur of black and white feathers going in and out. So much activity on a hot afternoon when most other wildlife was skulking, waiting for the sun to sink and the gloaming to begin.

Truth be known, the heat was too much for me too. Eventually I had to find shade beneath a willow and sit quietly until sweat stopped beading on my brow and my lungs – tightened by grass pollen – eased.

First visit to the Severn, remembered

Sitting there, watching the river sliding by and sensing my thoughts drifting with it, I was reminded of my first-ever visit to the river with rod and line. It was 1991 and I’d just read Chris Yates’ recently-published book The Deepening Pool. Suddenly the River Severn, which I’d seen hundreds of times before, took on a golden hue as I learned of fish called barbel. (I’d previously fished mostly for trout and wild carp.) Barbel, I had read, were not unlike wild carp in their feeding habits (barbel and carp like the same baits), both had golden scales and fought hard. But, wonder of wonders, barbel lived in flowing water, not lakes like their barbuled cousins. Indeed, they liked fast water where the current kept the riverbed clean and gravelly – much like the water I sought when fishing for trout.

Barbel – prince of the river

I discovered that one could fish for barbel via a number of means: trotting a float, trundling a bait through a likely-looking spot, or legering with a bait weighted to the bottom, then awaiting an arm-wrenching ‘wallop’ on the rod as a barbel took the bait. This was exciting fishing, where the hypnotic beauty and movement of the river would ‘only just' counteract the heart-pounding adrenaline that a fish could – at any second – turn one's day into sheer chaos as it attempted to pull the rod from one's hand and swim at juggernaught speed to the nearest snag. If I were to fish for them, I’d have to stay very, very alert. Barbel, like the mighty mahseer of India, can turn grown men into shaking wrecks. How, then, could a sixteen year old boy – who’d never coarse fished in a river before, cope with the challenge?

If I could settle my nerves, then all I’d need would be the same stalking outfit I used for wild carp (an avon rod, reel loaded with 8lb line, and a large deep-meshed landing net). And instead of freelining, as I would have done for wildies, I’d attach a leger heavy enough to hold bottom and then cast to a spot where fast water slows as it deepens into a pool. I knew of two such spots halfway between Hampton Loade and Alverley; one on a bend in the river and the second, just downriver, where the water passes around an island.

First quest for barbel

On a day in late July 1991 I set off from home with my fishing tackle strapped to my bicycle and everything else in a rucksack on my back. It took me an hour-and-a-half to cycle seven miles from home to the river, cross the river on the old ferry (ably operated by a little old lady), and then judder and bump my way along a 'tree-rooted' earthen path to the first of my two swims. The river at this point took a dog-leg bend to the left; the current flowered over boulders and almost directly into a bedrock bank before swirling in a pool and heading back along its course. It looked as though the water could be ten feet deep and the fish could be shoaled up in an undercut beneath my feet.

The Hampton Loade Ferry in 1991. Note the manicured lawns. Today it is difficult to see the river from this point as the bankside foliage is so high.

First cast

I tackled up my rod and line, then pushed a large cube of luncheon meat onto the hook. I cast twenty yards upstream, beyond the deeper water, then allowed the current to bring the line back to me. It settled about fifteen feet from the bank. I held the rod high, to keep as much line out of the water as possible, and began the wait for my first barbel.

The sensation of feeling the current on the line was something I’ll never forget. And the noise it made – like a simmering kettle on a range stove, was truly incredible. Every second was a new experience; every moment was one of hope.

And then the bite came. Without warning, the rod kicked in my hand. I stuck instantly and felt the heavy, dull, throbbing sensation of a fish pulling against the line in deep fast-flowing water. It kept kicking and jarring on the line, but felt almost like a dead weight compared to wild carp in a pond (which are more inclined to swim away at great speed). This fish hadn’t taken an inch of line off the reel. As I pumped the fish towards me, and saw it splash on the surface, I knew why the fight was so jarring – it was a chub of about two pounds. I netted the fish, unhooked it, and returned it to the river.

Not the barbel I was after, but my first-ever chub.

Second swim, first barbel

Believing the swim to be ruined by me playing a fish in it (unlikely, given the ‘cover’ afforded by the water tumbling over boulders) I elected to head on downriver to my second swim.

Here the bank was high, so I looked down to the river to see it swirling and boiling over boulders as it passed to the right of an island. This was a fast water, textbook barbel swim. (Although, considering it now, the water was probably too fast for big fish – which would have been holding sixty yards downriver in deeper water.) There were two current lines, in water that appeared to be approximately six feet deep.

The River Severn, right of the island at Hampton Loade. Classic barbel swim or Himalayan-style torrent?

This water – which seemed torrential – would require me to use a really heavy lead to hold bottom. Fortunately for me, my local tackle shop has advised me of the best types to use. They were called ‘meat legers’ and were the shape of a gravestone. The largest I could buy weighed two ounces. I’d purchased three of them, in case I lost some in the rocks, so I clipped one to a snaplink swivel on my line.

I then crept slowly down the bank (still thinking I was stalking carp) and readied myself to cast. I couldn’t believe the weight on the rod as I lined the rod up to cast. I’d never felt anything like it, having previously only freelined for carp or cast a fly-line to trout. It felt as through the rod tip could break under the weight of the lead, let alone the cast. But all was good as the lead and luncheon meat flew out and landed with a ‘kersploosh’ halfway between me and the island.

The lead held bottom and the line ‘sang like a kettle’ as the rod held the line against by the current. I could feel a constant vibration in the rod, though I wasn’t sure if this was from the river or from the blood pumping through my veins. Then the vibration became a tremble, then a pluck, then a jag then – whoosh! – the rod was pulled down parallel to the water and nearly out of my hand in the most savagely brutal bite I’d ever experienced. It felt like the river wanted to snatch me away and eat me whole. If I hadn’t had a secure foothold, I could easily have ended up in the river.

The fish, which had doubled the rod over and was making the line whistle in the wind, had turned against the current and was now heading downriver. It felt more like I was playing the river than a fish. So much power. Such seemingly unstoppable speed. It was like nothing I’d experienced before. I remembered Dick Walker’s words, as quoted in The Deepening Pool: “for the first few seconds, you don’t know if you’ve hooked a three or thirteen pounder”. This fish could have been three hundred pounds. There was no way of stopping its initial run.

I had no choice but to loosen the clutch on my reel and let the fish run downriver, out of the rapids. I then followed it along the bank, salmon fisherman-style, until I reached a line of rocks that went halfway out across the river. The water behind them was slow and deep, so it was here that I was able to turn and control the fish – which, by now, was tiring.

I pumped the rod towards me, gain line back on the reel. The fish was staying deep and circling in the deep water, but eventually I was able to bring it up the surface. There! There was my first barbel. Absolutely, definitely...a barbel. On my line. On only my second cast. And what a meal I’d made of playing it. The fish couldn’t have been more than two pounds. It was little more than a foot long. But it was a barbel!

Having realised that I hadn’t hooked a record fish, I gained confidence and played the fish harder until it was thrashing in my landing net. I brought it ashore, studied it, photographed it, and thanked it for the most exhilarating angling experience of my life.

As I slipped the barbel back into the water, I knew that this little fish – my first barbel – was not a baby but the grandparent of all that would follow. It had sparked something within me – an addictive rush – that would inevitably lead to an obsession that would shape my angling life.

My first-ever barbel: the one that inspired all others.

Back to present, and the legacy of that first barbel

As I sat there in the shade of the willow, I wondered if that little barbel was still alive. Perhaps it was now a double-figure specimen, coveted by every visiting angler? Or maybe it lived and died, but not before spawning new generations of barbel that are now the lifeblood of the river? I wished I could have had a rod and line with me there, right then, to meet one of its descendants. But that would have been premature. First we must have rain, lots of it, and second I’d need to cross the river and walk down to the swim beside the island to see, once again, where it all began. It will be my pilgrimage, my quiet moment with a loved one. And then, in the autumn, we’ll go fishing for barbel. All thanks to that little, warrior-hearted, fish.

If you like this blog, you'll like Fennel's book Traditional Angling.

If you like this blog, you'll like Fennel's book Traditional Angling.

Please also subscribe to the Fennel on Friday weekly email. You'll receive either a blog, video or podcast sent to you in time for the weekend.